Navigating Rates

After the trade war – time to assess a new era for global trade and cooperation

Markets are more sanguine now the threat of a trade war has diminished, but has President Trump’s gambit on tariffs created long-term vulnerabilities?

Key takeaways

- With the tariff threat partly resolved, investors are more optimistic about economic growth, and this creates a supportive backdrop for risky assets.

- But with employment growth falling, and consumers expected to bear the cost of tariffs, the risk of a US recession cannot be discounted.

- In the mid-term, there may be a case for a more selective approach to US assets.

As the dust settles on the latest salvo of tariff rates, and as it appears that most announced tariff rates are meant to last rather than being “invitations to negotiate” (Switzerland and India being the main exceptions), it’s time to summarise the new trade, economic and geopolitical world order that is emerging from the ashes of the old.

To be clear, we will still see changes, threats and “deals” going forward, but it appears we are now in a somewhat analogous period to the autumn of 2021, when the initial panic of the Covid-19 pandemic was giving way to a more pragmatic outlook. While case numbers, hospitalisation rates and vaccine effectiveness were still being closely followed – as are reciprocal tariffs, sectoral tariffs and investment promises today – the conversation was no longer dominated by a single topic, and investors were able to take a more general view of the developing environment.

Trump won?

It may be hard to admit, but US President Donald Trump seems to have pulled off what few thought possible: imposing massively imbalanced tariff rates with little in the way of retaliation. It is a “score” of 15% to 0% even in the case of the “best deals” such as with Japan or EU – and he received impressive-sounding headlines as sweeteners on top. (That said, it is unclear whether the USD 600 billion investments and USD 750 billion energy agreed with the EU, for example, will be any different in execution to the terms agreed with China in Mr Trump’s first term, which simply never materialised. If they did come to pass, investments on this scale in an economy already operating near full capacity could be less efficient and more inflationary.)

By threatening such high rates that would likely have pushed the US itself and a number of its trading partners into recession (especially in the case of broad-based retaliations), by conflating trade with many unrelated issues – most notably the security backdrop for the EU or Japan, for example – and by picking off his trade opponents one by one as they failed to coordinate in a textbook prisoner’s dilemma, Mr Trump was able unilaterally to reorder the rulebook of global trade.

Financial markets had initially revolted and forced him to change course on 9 April. Over the subsequent 90-day pause, however, the likelihood of recession and financial instability in the US seemed to decline. Excepting a brief episode with China, there was no meaningful retaliation by trade partners. Critically, the “Big Beautiful Bill” was passed in a more market-friendly form than initially feared – less fiscally irresponsible and without financial stability risks such as punishments for foreign holders of US assets. Although there are still concerns about the long-term impact of ballooning US debt, markets have grown more sanguine about US tariffs. Instead of a coinflip chance of recession, investors reverted to repricing US growth – down perhaps -1.5% over the next 2-3 years but cushioned by roughly +1% in stimulus from the bill, financed partly by tariff revenue – against a backdrop of inflation rising by roughly 2% over the same timeframe.

America lost?

While a big political win for Mr Trump, it is the US economy and especially its key engine, the US consumer, who could be the biggest losers in this new trade set-up. The last four months of US policy choices have arguably been a redistribution effort from ordinary Americans to wealthy Americans and corporations. It is US consumers, and predominantly the poorer part of the population, with high consumption rates, who will mostly pay for the tariffs – chiefly in the form of higher long-term inflation. In many cases, they will also forego healthcare access, while the wealthy will benefit from permanently lowered corporate taxes. Popular gestures, such as tax exemptions for tips, do not meaningfully change this equation; they are rather symbolic in proportion.

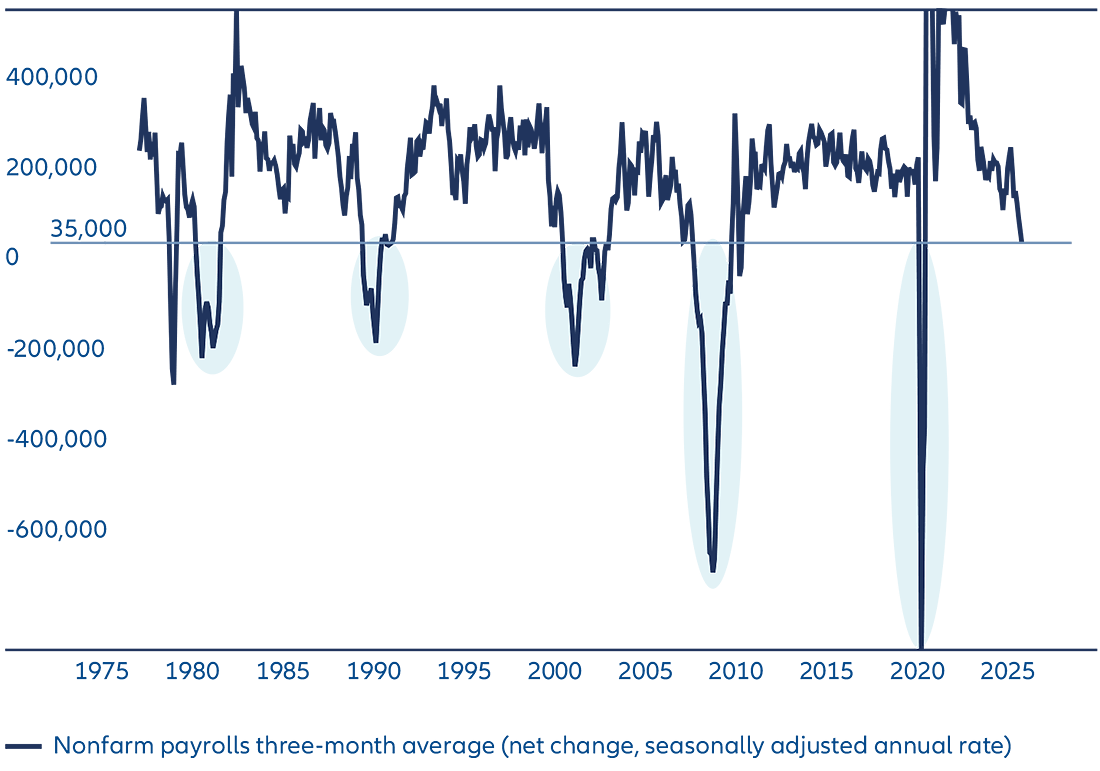

With the 1 August release of payroll data, and especially the revisions to the prior two months, it also looks like the economic damage of four months of severe uncertainty has been larger than assumed. The falling growth rate in the labour market is significant when put in historical context (Exhibit 1). US employment growth has rarely dropped this low – to an estimated 35,000 new jobs per month – without continuing into negative territory and signifying a recession.

Exhibit 1: Declining US employment growth can signal a recession

Source: Bloomberg.

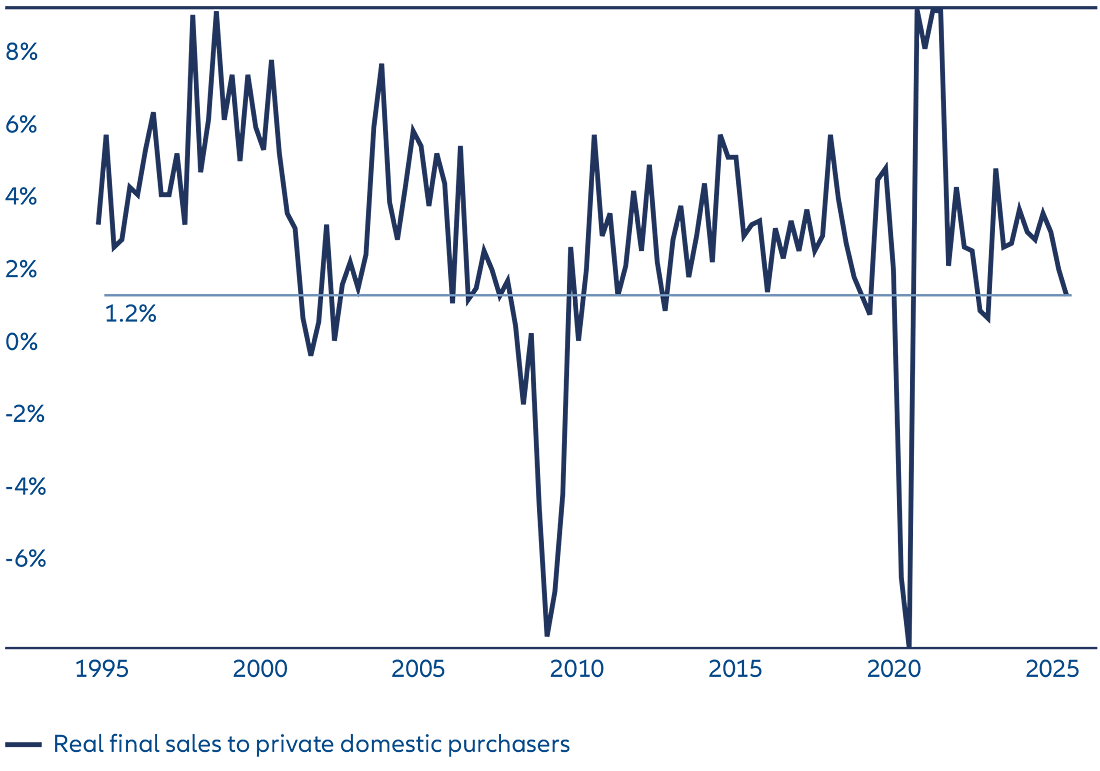

This data comes in addition to somewhat weak GDP growth in the second quarter. While the headline number held up at a +3% annualised rate, this was mainly due to distortions around import/export timing. The growth of “core GDP” of final sales to private domestic purchasers has been in continuous decline for three quarters. Its latest value was +1.2% annualised, which is likewise a level rarely reached apart from in the prelude to a recession (Exhibit 2). Recent exceptions – where core GDP growth dropped below 1.2% but there was no recession – were in 2022 and the end of 2018, which were difficult times for risky assets.

Exhibit 2: “Core GDP” growth at the current level can be precursor to a recession

Source: Bloomberg

A more predictable future is good for risky assets, and tariffs may still be challenged

Nevertheless, reduced uncertainty over tariffs and trade wars is positive for most economic actors and for risky assets, both in the US and globally. Tariffs reminiscent of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 are clearly less preferable than those in the 0-5% range and will simultaneously reduce growth and increase inflation, especially in the US; but, compared with expectations of just a few weeks ago, the absence of retaliation and increased predictability will benefit the economy.

In the immediate future, it seems likely the last tariff rates that are still at or above levels set on 2 April will fall – after some concessions to placate Mr Trump. Switzerland is the most likely next candidate. Canada, Mexico and China might also see their tariff rates decline if they keep offering political “wins” to the US president. Additionally, we expect to see some reversals in the data relating to US imports and international production as these numbers revert from their pre-tariff, front-loading levels.

Another point is that the legal status of most current tariff rates remains contentious, which suggests they could still be repealed. Executive orders using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) were based on “national emergencies” from “unusual and extraordinary threats”. These included: decades of trade deficits (underpinning “reciprocal” and “baseline” tariffs on all countries); fentanyl imports – specific to China, Mexico and Canda; and the prosecution of a former president (Brazil). Here the meaning of both “emergency” and “unusual”, as well as the legal authority of the president to address these issues using tariffs, is questionable. A legal challenge is currently being tried at the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals but expected ultimately to reach the Supreme Court.

But has the US lost allies?

Even if Mr Trump’s tariff regime were to evolve, however, its echoes might be felt for some time. “The Economic Consequences of the Peace” was a popular 1919 book by the economist John Maynard Keynes that argued that a peace agreement perceived as unfair by the losers of World War I would not be in the interests of the winners either. While he cannot have anticipated exactly what unfolded 20 years later, history proved his general conclusion right. Fortunately, today we are only looking at a trade war and nothing graver, but the one-sidedness of the “deals”, and the humiliation experienced by national leaders, raises the question what will be the economic consequences of the trade peace over a longer horizon.

The lessons learned in the last four months will stay with Mr Trump’s trade partners, at the very least fostering a desire to reduce exposure and reliance on the US. Perhaps they will also aim to unite with others and seek payback. Transforming a world where most key actors were committed US allies into one inhabited by antagonists, within just four months, would be an astonishing loss of soft power.

Attacking allies abroad has also been flanked by a domestic campaign against independent institutions. Mr Trump fired the chief of the Bureau of Labor Statistics after the July jobs report revealed employment growth had stalled. He has also attacked the Federal Reserve (Fed). These sorties risk further eroding the trust of financial markets and institutions in the US.

This leads to a key question, which is made urgent by these longer-term deteriorations: if the US were to edge closer to a recession, what arsenal does it have to fight it? The debt-to-GDP ratio stands at 120% and budget deficits have been running at -6% a year, while inflation is exposed to unusual upward pressure from tariffs even in a slowdown scenario. US policymakers might face two unenviable choices: strict austerity that would extend the duration and severity of a slowdown; or, let inflation overshoot target while monetising fiscal stimulus. The latter option, which would require a more compliant Fed than is currently in place, could open the door to long-term stagflation.

After a short-term boost, a selective approach to the US may be wise

If US macro data stays at least ambiguous in the short term, global and perhaps even US stocks could benefit. As well as falling uncertainty, there are positive drivers in many regions such as corporate earnings growth, German fiscal stimulus and tailwinds from monetary policy.

Mid-term, however, there may be a stronger case for taking a more selective position on the US – in both equities and currency. Investors in the US and globally remain overweight US assets, especially equites, and these stocks still trade at premium valuations, not only in innovative growth companies but across the board. This makes for an uncomfortable starting point. A slowdown in the US economy, without sufficient fiscal space for appropriate countermeasures, would be a challenging scenario to navigate.

Would a US downturn spill over in all regions of the world? Currently, Europe and Asia look comparatively stable. Due to tariffs, both regions will experience a certain decoupling either way – and this could blunt the marginal impact of lower US demand, should there be an economic slowdown. Each region retains a reasonable degree of fiscal space to support their economies if need be. So, there exist buffers as well as tools to manage a slowdown in growth – though a full-blown US recession would almost certainly lead to a broader risk-off scenario.

In the short term, it seems Mr Trump’s gambit on tariffs has not troubled the outlook for risky assets. In the long term, by ending a decades-long period of global trade liberalisation and integration, he may have introduced a number of complex risks that investors will have to navigate for years to come.

4764453